Why Is Fudō Myōō So Popular? Meaning, Devotion, and Everyday Resonance

Quick Summary

- Fudō Myōō is popular because he represents steadiness under pressure: a calm, immovable center when life feels chaotic.

- His fierce appearance is widely read as protective rather than aggressive, which makes devotion feel practical and close to daily life.

- People connect with the idea of “cutting through” confusion, habits, and fear—especially in work, relationships, and stress.

- He is associated with discipline and follow-through, which resonates in a culture of distraction and constant demands.

- His imagery is memorable and emotionally direct, making it easier to feel a relationship with the symbol.

- Devotion often grows where a figure feels both uncompromising and compassionate—firm, but not rejecting.

- Fudō Myōō’s popularity endures because the human need for inner stability does not go out of date.

Introduction

If you’re trying to understand why Fudō Myōō is so popular, the confusion usually comes from the contrast: he looks wrathful, yet people speak of him with trust, closeness, and even relief. That gap—between fierce imagery and everyday comfort—is exactly where his meaning lands for many people, because life often requires a kind of kindness that is firm enough to hold the line. This explanation is written from a Zen-informed, practice-oriented perspective at Gassho, focused on lived experience rather than theory.

Fudō Myōō (often rendered “Acala,” the “Immovable One”) is frequently approached not as an abstract idea but as a felt presence: a symbol of stability when emotions surge, when decisions are hard, and when old patterns keep repeating. Popularity, in this sense, is not about trend—it’s about usefulness.

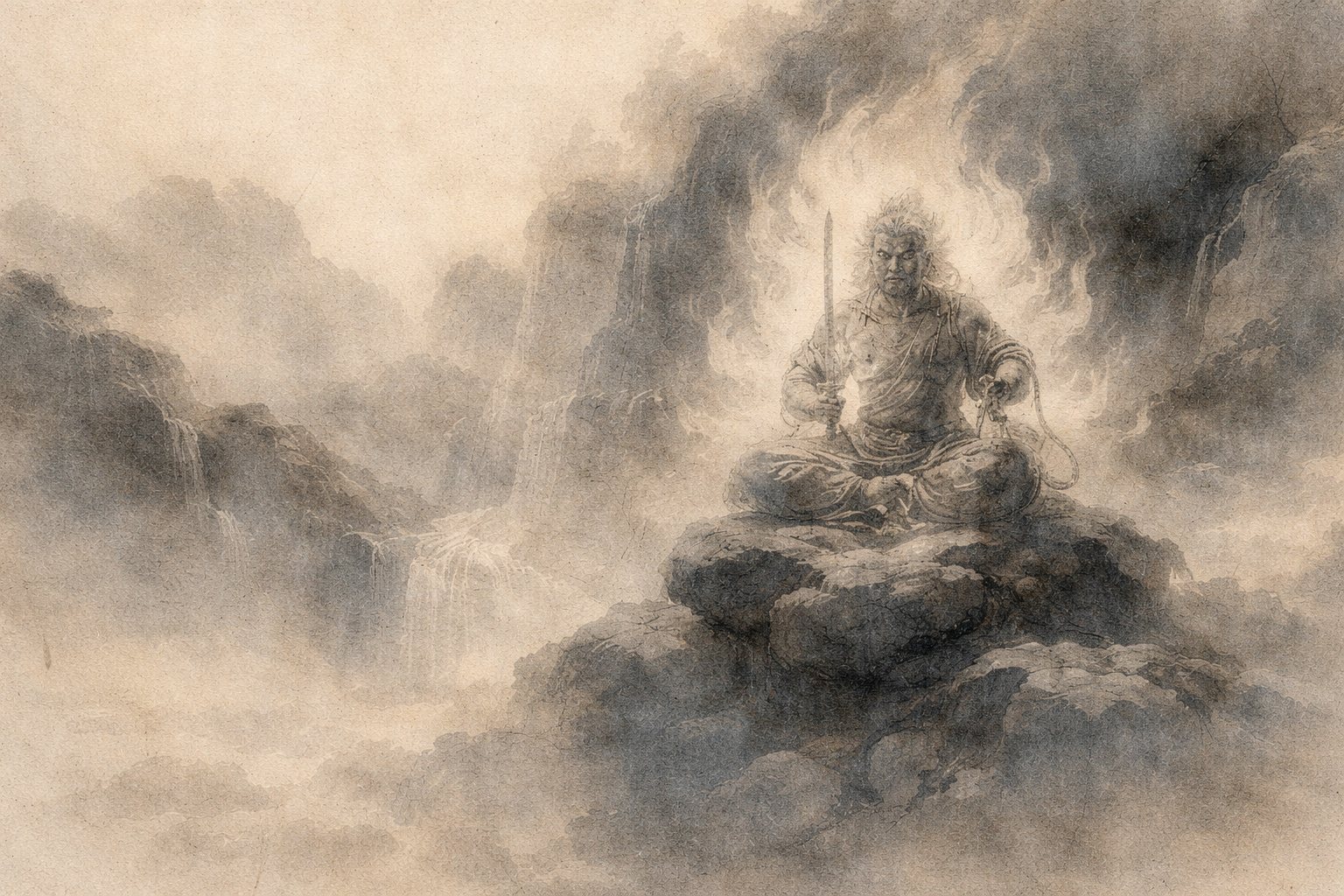

His iconography can look intense at first glance: a stern face, a sword, a rope, flames. Yet many devotees interpret these as compassionate functions—cutting through what harms, binding what runs wild, burning away what obscures. The popularity starts to make sense when those functions are recognized in ordinary life.

The Lens: Why Fierceness Can Feel Like Care

A helpful way to understand Fudō Myōō’s popularity is to see him as a mirror for a human need: the need for a steady center that does not negotiate with confusion. In daily life, there are moments when gentle encouragement is not enough—when the mind keeps circling, when fear keeps bargaining, when fatigue keeps postponing what matters. The “immovable” quality points to a kind of inner reliability.

His fierce expression can be read as the face we wish our clarity could have when we are tempted to abandon ourselves. Not harshness toward a person, but firmness toward what entangles: the spiraling story, the reactive message, the familiar avoidance. In that reading, fierceness is not violence; it is refusal to be pulled off-center.

This is why the symbolism often feels surprisingly intimate. People do not always want a comforting image when they are overwhelmed; sometimes they want something that can stand up to the overwhelm. Fudō Myōō becomes popular because he embodies a strength that does not depend on mood.

Even without specialized knowledge, the basic message is accessible: there is a way of being present that does not collapse into anger, panic, or numbness. The popularity grows where that message feels like a realistic description of what life asks for—at work, at home, and in the quiet moments when no one is watching.

How Devotion Shows Up in Ordinary Moments

In a stressful workday, the mind often tries to escape into speed: quick replies, multitasking, tightening the jaw, pushing through. The appeal of Fudō Myōō here is not mystical. It is the simple recognition that steadiness is a form of protection. When attention stops scattering, the situation is still difficult, but it becomes less consuming.

In relationships, the most painful moments are often the smallest ones: a tone of voice, a delayed response, a familiar misunderstanding. Reactivity arrives fast, and then the story builds itself. Fudō Myōō’s popularity connects to the wish to pause inside that speed—to feel the heat of emotion without immediately turning it into speech that cannot be taken back.

During fatigue, the mind can become permissive in a way that doesn’t feel like freedom. It says yes to what drains, no to what nourishes, and later calls it “just how things are.” The “immovable” image resonates because it suggests a different kind of no: not a defensive no, but a clear boundary that keeps life from being run entirely by momentum.

In silence—on a commute, before sleep, in the early morning—there can be a subtle discomfort that appears when there is nothing to distract us. Many people discover that the mind does not automatically become peaceful when things get quiet; it becomes loud in a different way. Fudō Myōō’s fierce calm can feel like permission to stay present without needing the mind to be pleasant first.

When someone is trying to change a habit, the struggle is rarely dramatic. It is repetitive. It is the same urge, the same justification, the same “tomorrow.” The sword and rope imagery often lands here as a plain psychological truth: sometimes clarity needs to cut, and sometimes it needs to hold. Not as punishment, but as care that is willing to be firm.

Even the flames—so striking in statues and paintings—can be experienced in a very ordinary way: the feeling of being “burned” by consequences, by honesty, by seeing clearly what has been avoided. People often turn toward Fudō Myōō not because they enjoy intensity, but because they sense that intensity is already present in life, and they want a way to meet it without being consumed.

Over time, popularity can come from reliability. A symbol that consistently points back to steadiness becomes something people return to when they are scattered. Not because the symbol fixes life, but because it reminds the mind of a posture it recognizes as sane.

Misreadings That Make Fudō Myōō Seem Distant

A common misunderstanding is to take the fierce face literally, as if devotion were about anger or intimidation. That reading is understandable because the imagery is strong, and many of us have learned to associate strength with threat. But the popularity of Fudō Myōō suggests that many people experience the opposite: a protective firmness that feels safer than vague reassurance.

Another misreading is to treat the figure as a promise of control—over other people, over outcomes, over life’s uncertainty. When life feels unstable, the mind naturally looks for something solid to hold. Yet the “immovable” quality can also be understood as inner steadiness in the middle of change, not the elimination of change.

Some people also assume devotion must be dramatic to be real: intense rituals, intense feelings, intense certainty. In practice, what often sustains popularity is the opposite—quiet repetition, a simple sense of being accompanied, a reminder that clarity can be firm without being cruel. The mind gradually learns what it is actually asking for.

And sometimes the misunderstanding is subtler: thinking that fierceness is incompatible with compassion. In ordinary life, compassion often has to include boundaries, honesty, and the willingness to disappoint expectations. Fudō Myōō remains popular because he gives that difficult compassion a face people can recognize.

Everyday Resonance: Why the Symbol Keeps Working

Modern life rewards speed, performance, and constant availability. In that atmosphere, a symbol of immovability can feel like a quiet counterweight. Not as an escape from responsibilities, but as a reminder that being pulled in every direction is not the same as being alive.

There are also ordinary moments when people sense they are drifting from their own values: saying yes too quickly, speaking too sharply, numbing out at the end of the day. The popularity of Fudō Myōō often lives in those moments—not as a dramatic intervention, but as a steady reference point that makes drifting easier to notice.

In families and workplaces, many people carry roles that require calm strength: parenting, caregiving, leadership, showing up when tired. The fierce-but-still image resonates because it reflects a kind of strength that is not performative. It is simply there, doing what needs to be done without needing applause.

Even aesthetically, the iconography has an everyday function: it is hard to ignore. A gentle symbol can fade into the background when the mind is busy. A fierce, grounded presence tends to cut through distraction. Popularity sometimes comes from that simple fact: the image keeps reminding.

Conclusion

Fudō Myōō’s popularity points to something ordinary and enduring: the wish to be steady without becoming hard. In the middle of heat—work, relationships, fatigue—there can be a quiet recognition of what does not need to move. The rest is verified in the next moment of daily life, exactly as it is.

Frequently Asked Questions

- FAQ 1: Why is Fudō Myōō popular in Japan compared to other Buddhist figures?

- FAQ 2: Why is Fudō Myōō popular even though he looks angry or frightening?

- FAQ 3: Why is Fudō Myōō popular for protection and safety?

- FAQ 4: Why is Fudō Myōō popular among people facing obstacles or bad luck?

- FAQ 5: Why is Fudō Myōō popular for self-discipline and breaking bad habits?

- FAQ 6: Why is Fudō Myōō popular with people who feel anxious or overwhelmed?

- FAQ 7: Why is Fudō Myōō popular in temples and mountain practice settings?

- FAQ 8: Why is Fudō Myōō popular in art and statues compared to gentler-looking deities?

- FAQ 9: Why is Fudō Myōō popular for fire rituals and purification themes?

- FAQ 10: Why is Fudō Myōō popular with business owners and workers?

- FAQ 11: Why is Fudō Myōō popular with families and parents?

- FAQ 12: Why is Fudō Myōō popular outside Japan as well?

- FAQ 13: Why is Fudō Myōō popular if Buddhism emphasizes compassion?

- FAQ 14: Why is Fudō Myōō popular for “cutting through” confusion—what does that mean in daily life?

- FAQ 15: Why is Fudō Myōō popular for people who feel spiritually “stuck”?

FAQ 1: Why is Fudō Myōō popular in Japan compared to other Buddhist figures?

Answer: Fudō Myōō is popular in Japan because he is widely experienced as practical: a figure associated with protection, steadiness, and follow-through in everyday concerns. His presence is also highly visible in temples, local devotional sites, and cultural art, which keeps the relationship close and familiar rather than distant or purely philosophical.

Takeaway: Popularity often follows what feels usable in daily life.

FAQ 2: Why is Fudō Myōō popular even though he looks angry or frightening?

Answer: Fudō Myōō is popular because many people interpret his fierce appearance as protective strength rather than hostility. The intensity can feel like a promise of firmness against what harms—fear, confusion, and destructive impulses—especially when gentle imagery doesn’t match the intensity of real-life stress.

Takeaway: Fierce imagery can communicate safety through strength.

FAQ 3: Why is Fudō Myōō popular for protection and safety?

Answer: Fudō Myōō is popular for protection because he symbolizes an unshakable presence that “stands guard” when life feels unstable. Devotees often relate to him as a protector in ordinary risks—travel, health worries, workplace pressure—where what’s sought is steadiness and reassurance rather than dramatic change.

Takeaway: Protection can mean feeling grounded in uncertainty.

FAQ 4: Why is Fudō Myōō popular among people facing obstacles or bad luck?

Answer: Fudō Myōō is popular in difficult periods because he represents the capacity to meet obstacles without collapsing into panic or avoidance. When people feel “blocked,” the image of immovability can be emotionally stabilizing, helping them feel less alone with the pressure of circumstances.

Takeaway: The symbol resonates when life feels heavy and repetitive.

FAQ 5: Why is Fudō Myōō popular for self-discipline and breaking bad habits?

Answer: Fudō Myōō is popular for discipline because his symbolism is uncompromising: clarity that cuts through excuses and steadiness that doesn’t drift with mood. Many people relate to this when trying to change habits, keep commitments, or stop repeating patterns that feel harmful but familiar.

Takeaway: Popularity grows where firmness feels like compassion toward oneself.

FAQ 6: Why is Fudō Myōō popular with people who feel anxious or overwhelmed?

Answer: Fudō Myōō is popular with anxious or overwhelmed people because he embodies steadiness in the presence of inner “heat.” Rather than requiring calm first, the image suggests a calm that can coexist with intensity, which matches how anxiety is often actually lived.

Takeaway: The appeal is steadiness that doesn’t depend on perfect conditions.

FAQ 7: Why is Fudō Myōō popular in temples and mountain practice settings?

Answer: Fudō Myōō is popular in these settings because his symbolism aligns with endurance, focus, and protection in demanding environments. Mountain and temple contexts often emphasize perseverance and clarity, and Fudō Myōō’s “immovable” quality naturally fits that atmosphere.

Takeaway: The setting reinforces the meaning of steadiness under pressure.

FAQ 8: Why is Fudō Myōō popular in art and statues compared to gentler-looking deities?

Answer: Fudō Myōō is popular in visual culture because his iconography is immediately recognizable and emotionally direct. The strong posture, intense face, and dynamic elements like flames create a memorable symbol that can “cut through” distraction, making the figure feel present even in a brief glance.

Takeaway: Strong imagery can function as a strong reminder.

FAQ 9: Why is Fudō Myōō popular for fire rituals and purification themes?

Answer: Fudō Myōō is popular in connection with fire and purification because flames naturally symbolize intensity that transforms: heat that reveals, burns away, and clarifies. Many people find this meaningful when they want to let go of what feels sticky—resentment, confusion, or lingering regret—without needing to turn it into a dramatic story.

Takeaway: Fire imagery resonates with the wish for clarity and release.

FAQ 10: Why is Fudō Myōō popular with business owners and workers?

Answer: Fudō Myōō is popular with workers because daily work often demands steadiness, decisiveness, and resilience through stress. His symbolism can feel like support for staying grounded under deadlines, conflict, and uncertainty—less about “winning” and more about not being internally shaken.

Takeaway: The workplace is a common place where immovability feels relevant.

FAQ 11: Why is Fudō Myōō popular with families and parents?

Answer: Fudō Myōō is popular with families because parenting and caregiving often require calm firmness: protecting, setting boundaries, and staying steady through emotional storms. His fierce-but-protective presence can mirror the kind of strength people hope to embody for those they care about.

Takeaway: Devotion can grow where protection and responsibility meet.

FAQ 12: Why is Fudō Myōō popular outside Japan as well?

Answer: Fudō Myōō is popular beyond Japan because the core human experience he points to—wanting steadiness amid pressure—is universal. Even when cultural details differ, the emotional logic of the symbol is easy to recognize: a grounded presence that does not flinch.

Takeaway: The need for inner stability crosses cultures.

FAQ 13: Why is Fudō Myōō popular if Buddhism emphasizes compassion?

Answer: Fudō Myōō is popular because many people understand compassion as more than softness. In real life, compassion can include boundaries, honesty, and the strength to stop what causes harm. His fierce form can be felt as compassion that is strong enough to protect.

Takeaway: Compassion can look firm when it needs to be effective.

FAQ 14: Why is Fudō Myōō popular for “cutting through” confusion—what does that mean in daily life?

Answer: Fudō Myōō is popular for “cutting through” because confusion often feels like mental noise: overthinking, second-guessing, and reactive narratives. In daily life, “cutting through” can simply mean recognizing the moment the mind starts spinning and returning to what is actually happening—one conversation, one task, one breath at a time.

Takeaway: The appeal is clarity that interrupts spirals.

FAQ 15: Why is Fudō Myōō popular for people who feel spiritually “stuck”?

Answer: Fudō Myōō is popular for feeling “stuck” because his symbolism emphasizes immovability without stagnation: a stable center that can face discomfort directly. When people feel they are repeating the same inner patterns, the fierce steadiness can feel like a reminder that clarity is possible even in the middle of repetition.

Takeaway: Being “stuck” often calls for steadiness more than novelty.